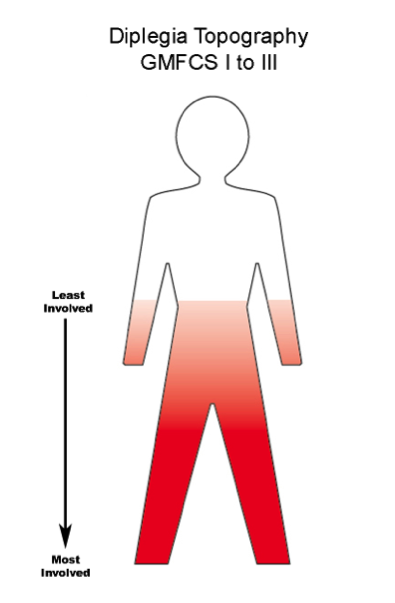

In spastic diplegia, the lower leg muscles are the most involved part of the body. Spasticity is most severe in the lower leg and it becomes less problematic as you move up the body. Overall, 98% of children with diplegia are labeled as GMFCS Levels I to III with only 2% in Level IV and V.

Will My Child Walk? Are We Doing the Right Therapy?

What is the brain pathology and what does it mean?

Spastic diplegia is caused by Periventricular Leukomalacia (PVL) or Germinal Matrix bleeds that extend outward into the white matter. These are most commonly found in babies less than 32 to 34 weeks gestation. This link gives a full description and a diagram showing the location of the damage.

Spastic Diplegia – Cure For Some, Improvement For All

If the damage is bilateral, both legs are involved, but it is very common to have one leg more involved than the other due to asymmetrical brain injury. In children with brain scan diagnosed PVL, very severe lesions are predictive of later problems, but those with a moderate degree of PVL on scan have a variable outcome, with a significant number of brains with apparent recovery in the first few years. Mild PVL changes were not associated with a poor outcome.1

What improvements are possible with repair, growth and maturation of the brain?

All children with Level I and II are able to walk and run and usually the run is better than the walk. This is because the walking pattern was learned early with a damaged, immature brain in the process of recovery. The later learned run demonstrates that the brain has actually recovered…remember, we walk and run with the same parts of our brain. If the more complex running skills are near normal or better, you can confidently say that the walk is a habit and habits can be changed… with the right work.

The Boy Who Could Run Better Than He Could Walk

These children need early, active spasticity management, starting with control of tone at the ankle joint. They are expected to do well and as a result, many times they are not treated aggressively in the early years. There is no point in waiting to treat it until it is bad enough.

Do You Want Your Child to Walk or to Walk Well?

If the early opportunity is missed, remember that the brain is wonderfully neuroplastic and positive change is possible at any age.

An Intensive Experience by Erik Zimmerman – Adults with CP can Improve

What are the risks of other sensory or brain problems?

The more premature the baby, the higher the risk of vision, hearing and cognitive problems. These are NOT caused by the PVL or germinal matrix bleed. The white matter damage only causes motor and sensory-motor problems, not damage to vision, hearing or intelligence.

Vision Most premature babies have screening for Retrolental Fibroplasia (RLF) changes in the nursery, but an ophthalmologist should check their eyes annually until they are through puberty. Myopia or short sightedness is a common problem. How well the child focuses both eyes to work together is also important and often an optometrist can help. Remember, annual examinations by eye experts.

Can My Child See? Have We Had The Right Assessments?

Hearing These problems are rare, but they do still occur. If there is any speech delay, get the hearing checked by an expert. This should be repeated every 2 to 3 years through childhood, especially if the child has frequent ear infections.

Cognition Severe cognitive problems are very rare in this group of children with diplegia. Some developmental learning difficulties in the early school years may occur, more in boys and more in babies born in the extremely pre-term range <25 weeks. This is a readable summary about learning disabilities (LD) that all parents of a child with cerebral palsy should read: The State of Learning Disabilities by the National Center for Learning Disabilities. 2

The important points to remember if your child with diplegia is struggling at school are:

- Eye check – ophthalmologist and a specialist in prism adaptation techniques.

- Hearing check – a high tone hearing impairment, common in children born prematurely, is important to treat. With it, car, far, bar and star all sound like “ar”. What they hear is similar to a “hard of hearing” adult.

- Learning Issues – these children should get the same diagnostic and educational help as with all able-bodied children. All too often the LD is assumed to be part of CP. It is not. It is a co-existing problem, not linked to the PVL damage. The children will respond to educational help and their parents should demand it. Your pediatrician can be a great help in getting these services for this common pediatric problem. The experts are found in the educational, not the CP professional silo.

What therapies and treatment have the most research back up?

In these journal articles by Iona Novak, “A systematic review of interventions for children with cerebral palsy: state of the evidence”3 and “Evidence-based diagnosis, health care, and rehabilitation for children with cerebral palsy”4 are the evidence based and best practice therapies and interventions where there is good enough research data to support their use and insurance coverage. This is the basic stuff you really have to know and understand. I would strongly advise you to bring these citations to your healthcare team and then go over the recommendations to see which ones are right for your child.

My experience with diplegia is that you can determine the probable level of involvement by 2 to 3 years at the latest. The very mild GMFCS Level I children do well with good physical therapy, compressive garments, properly fitted AFO’s and in some cases, Botox.

Take Advantage of the Periods of Peak Neuroplasticity

Child active therapies such as Hippotherapy, water exercise, and many different types of gait training are helpful. Adaptive sports start early and help throughout the teen years. Many teens at this level will graduate to able-bodied sports as their body and brains mature.

Children at all other levels need more than these basics. Remember, the outcome levels in diplegia are good with a wide variety of early interventions. But parents have to remember that all children, even those most severely involved, all improve in the first years of recovery and peak neuroplasticity. I believe it is important to develop a long-range view and set your goals higher than GMFCS Level I to III. At the least, I would want all those at GMFCS Level III to be a II, all those at Level II should go for a Level I and all those at Level I should function well within the normal range.

We know what happens without active spasticity management to children with diplegia. The spasticity progresses with each growth spurt. None of the GMFCS long-term study sample children had Botox, a Selective Dorsal Rhizotomy (SDR) or a Baclofen Pump. Orthopedic management was not what it is today. Teenagers at Level I and II stayed the same and the level III teens got worse.5

I would like some of my readers to write in their experiences with change over time. Younger parents need your input to understand the value of doing more earlier. Older teenagers and adults need to know that change is still possible. If you are told that your child has plateaued, what this really means is that the therapist or physician does not know how to improve function to a higher level. I respectfully suggest you look elsewhere for help.

See Also – GMFCS and Topography Series

1.What Is Your Child’s Label?

2.Cerebral Palsy – The Best Possible Outcome and How To Get It

References:

- Lara M. Leijser et al., “Comparing brain white matter on sequential cranial ultrasound and MRI in very preterm infants”, Neuroradiology, 50 (2008): 799-811 http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00234-008-0408-4#/page-1

- Candace Cortiella and Sheldon H. Horowitz, The State of Learning Disabilities: Facts, Trends and Emerging Issues (New York: National Center for Learning Disabilities, 2014) https://www.ncld.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/2014-State-of-LD.pdf

- Iona Novak et al., “A systematic review of interventions for children with cerebral palsy: state of the evidence”, Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology, 55 (2013): 885-910.

- Iona Novak, “Evidence-based diagnosis, health care, and rehabilitation for children with cerebral palsy”, Journal of Child Neurology, 29 (2014): 1141-1156.

- Steven E. Hanna et al. “Stability and decline in gross motor function among children and youth with cerebral palsy aged 2 to 21 years.” Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology, 51 (2009): 295-302.

My son has pVl but he does have vision problem known as CVI. You make no mention of CVI in your article yet this is something that CAN and does go with pVl damage?? Grateful for your views on this…

Thank you for your question Zoe, it is a good one. My point is that PVL in the main affects the “wiring” of the motor control system. This is what causes diplegia. In babies born very early, less than 28 weeks, the area of PVL is further back in the brain and can affect some of the visual connections, but this is rare. CVI is a somewhat basket term that is primarily related to damage to the occipital lobes of the brain. These are most commonly damaged in more mature babies with Neonatal Encephalopathy (NE) or Hypoxia Ischemic Encephalopathy (HIE) I will be talking more on Visual impairments in future posts. When you have unusual associations,it is worth double checking to see if the eye problem could be caused by something else.