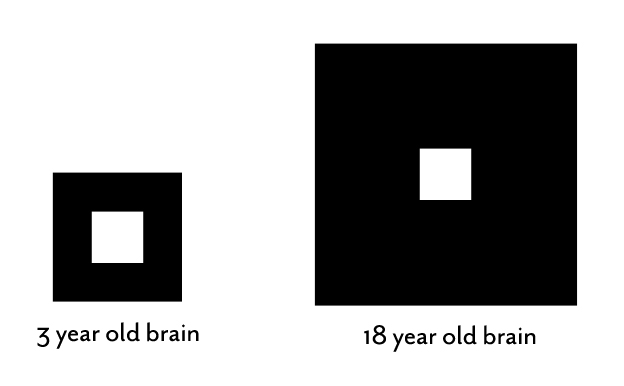

This diagram represents the relative size of a three-year-old brain compared to an 18-year-old brain. I picked a three-year-old brain because this is the age when most children are diagnosed with cerebral palsy. The square hole in the center of the first diagram represents an area of brain damage. It looks pretty big compared to the amount of normal brain. Fifteen years later, after the pubertal brain growth spurt, the brain is a lot bigger and a lot more complex, but the amount of damaged brain remains the same. In the diagram, it looks as if the area of brain damage has shrunk, but if you measure the two squares, they are the same size. The difference is that the child at 18 has a lot more normal brain real estate.

Brain damage in children with cerebral palsy is a time-limited event. Whatever caused the problem – a bleed, a stroke, an infection or a missed bit of early brain development – it is not progressive. The damage is what it is. This means that babies have an enormous advantage and actually more potential for improvement than an adult with a similar amount of brain damage. The damage may stay the same, but the brain keeps growing and maturing.

The three-year-old child, being diagnosed with cerebral palsy, has fallen behind in the development of the motor, language and/or thinking skills of an average three-year-old child. By this age, they have also developed abnormal movement patterns. Each individual child’s brain damage has interfered with one or more of these three important areas of development. The important thing to realize is that the brain keeps growing and maturing new functions. The three-year-old child has much less brain than the 18 year old teenager.

The title of my book, to be released September 20, 2016, is The Boy Who Could Run But Not Walk: Understanding Neuroplasticity in the Child’s Brain. The title is taken from the common observation that the vast majority of children with hemiplegia can run better than they can walk. You can even measure the difference in a gait lab.1,2 It took me a long time to realize that children with early brain damage learn to walk with a damaged, immature brain, but they learn to run with a recovered, more mature brain.

In the next few weeks, I will write more of what we know about baby brain neuroplasticity, brain recovery, brain maturation, and probably most importantly, how babies and children can rewire their brains using activity-dependent neuroplasticity. I have learned that at each stage of growth and maturation, it is possible to uncover evidence of brain recovery hidden by early-learned habits. It is not rocket science. It just requires a new way of seeing the totality of an individual child’s function.

1. J.R. Davids, A.M. Bagley and M. Bryan, “Kinematic and kinetic analysis of running in children with cerebral palsy.” Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology, 40 (1998): 528–535.

http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1469-8749.1998.tb15411.x/abstract

2. Marco Iosa et al, “Ability and stability of running and walking in children with cerebral palsy.” Neuropediatrics, 44 (2013): 147-154.

https://www.thieme-connect.com/DOI/DOI?10.1055/s-0033-1336016

Dr. Pape, are you still working with Threshold Electric Stimulation? I attended one of your courses with this approach/device many moons ago and wondered if you are still using it or have published any other articles about it.

Many thanks for all you do for these children!

MlStilwell

Thanks for your comment Mary Lou,Unfortunately TES has gone the way of many innovations in Pediatric Neurorehabilitation. It is no longer available. In fact, even EMPI, that had a dominant position in the NMES field recently disbanded that whole division of the company.It is too bad because both TES and NMES have a useful place in rehabilitation.

Have you ever worked with neuromodulation therapy?

Hi Heather, There are many techniques that fall under the rubric of neuromodulation. I have seen some terrific responses with both deep brain stimulation for movement disorders and vagal stimulation for persistent seizures.The key is patient selection. There are other groups that are using electrical stimulation for many diverse problems, but I am not familiar with them. Best wishes, Karen

I’m so interested in reading this. My son had a stroke in utero, which we learned about when he was 9 months old. He was not meeting any milestones at that time, and we were told, by phone call, mind you, that he had suffered a massive stroke and his entire left frontal lobe was atrophied. We were told he may never talk or walk, may always need care, etc. He’s 13.5 half now, in 8th grade, can run a sub-14 minute mile and shows no outward signs of his injury. He has difficulty processing math and reading; it takes him a little longer to grasp concept than his peers, but we figure that’s a small price to pay in exchange for the prognosis we were given early on.

Hello Bri, actually, your experience is not that uncommon. Next week I am posting a blog on Half a Brain, Children who have half their brain removed surgically may do extremely well. Babies with an intrauterine stroke are often well off as well. Slow with early milestones, but then the brain figures out how to rewire itself to allow function. I wish someone would look more closely at these outliers….it may reveal something to help all the others. If possible, I would love it if you would go back to where he was diagnosed and have them see him now. People will never learn if they do not know when they are wrong. You might want to read Soft W

ired by Michael Merzenich, the father of modern neuroplasticity. He and his team have developed a wide variety of brain training techniques to help with reading and other learning skills. At 13.5y your son is entering the pubertal brain and body growth spurt and it would be a good time to try a new approach.

Thank you, Karen. I will definitely look into that book as well. I don’t even know where to begin to have him seen by the office that originally diagnosed him, but I will see what I can find out!

Dear Karen. Our daughter was born with cCMV. Her brain hasn’t developed properly because of the virus. The MRI shows polymicrogyria, enlarged lateral ventricles and white matter damage. She’s now 2 and half and doesn’t roll, crawl, or sit despite our intensive physio exercises and a lot lot stimulation. She’s beautiful but somehow empty, her brain just doesn’t think… I’m losing my will to continue the everyday hard work. She’s the reason why we’ve decided not to have another child so I can devote my life to her but with no feedback it’s waste of time and my life. Is there anything to give her brain a kick at all? Thank you.

The questions you have are difficult and I am so sorry for all that you are going through. I think the best course of action might be to sit down and have a frank conversation with your physician and probably also a neurologist. The question you want to have answered is how much normal brain is there? It sounds like you have done all the right things to try and stimulate her brain. Now I would ask the experts for some guidance on next steps.

Thanks Karen. The professionals aren’t positive at all. She’s had the MRI when she was 6 months old and whatever they warned me might happen is really happening, no rolling, crawling, sitting, communicating, learning. To be fair there is some learning but it’s next to nothing. Oh well, I guess that’s it for us….

I am sorry to hear about your daughter’s condition.It is a true tragedy when the brain is that damaged. My thoughts are with you in this difficult time.