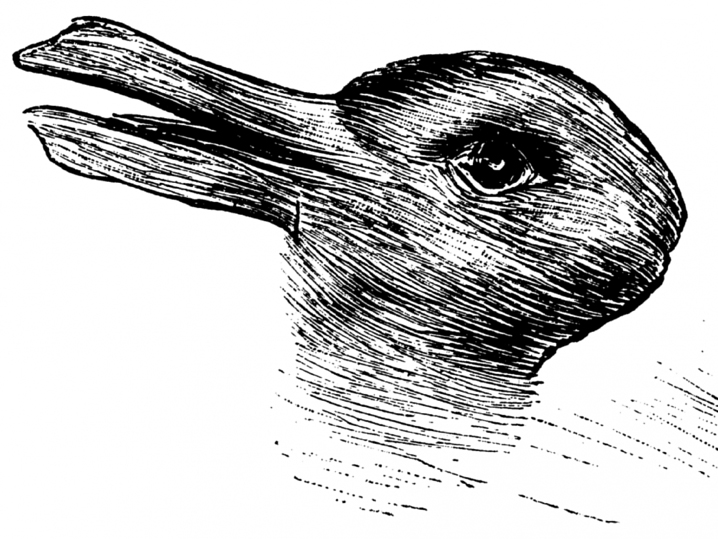

Look to the right and it is obviously a rabbit; look to the left and it becomes a duck. This perceptual image is a great example how our brains actively screen what we see. Our brains are efficiency driven and as a result, we most often see what we expect to see. The unexpected is often ignored until it is pointed out.

Why is this important in the child or adult with cerebral palsy?

Last week I wrote about the progressive maturity of the child’s brain from birth through puberty. (Test and Test Again Brains Keep Growing) Looking at the change in colors in the brain’s images, it is very clear that the teenage brain is capable of far more than the baby brain. Unfortunately, this obvious fact is frequently ignored in the child with a cerebral palsy diagnosis. In many cases, we continue to see what we expect to see – a child with a diagnosis of hemiplegia, diplegia or quadriplegia – and as a result, our brains do not actively consider that the child’s brain has been growing and maturing over time. New functional capability should be possible.

The CP diagnosis does not change, but the brain does.

The original brain malformation or injury that created the characteristic patterns of movement abnormalities that we call CP does not get worse as the child grows older. By definition the brain damage is not progressive. In fact, most children show improvement in their functional skills over the first 3 to 6 years of exuberant neuroplasticity and spontaneous brain recovery. Why don’t they continue to gain in motor skills?1 The traditional experts say that the skill levels plateau and justify their opinion by saying that CP is a permanent lifelong condition.2

I respectfully disagree.

I think this is another example of seeing what you expect to see. Taking the easy way out instead of asking, “Why are they not improving?” We know that their brains have recovered to whatever extent they can and they have grown and matured. So the question must be, “Why do they plateau?”

Permanent Problem or Treatment Failure?

In my view, the one overarching reason for the lack of functional improvement is the common treatment failure of only looking at the usual parts of the neurological examination. We carefully look at the child’s walk, we measure the joint range of movement and in many cases we even do a gait lab to more accurately examine the walk. But as I explain in my upcoming book, most children in GMFCS Levels I and II run better than they walk. (The Boy Who Could Run But Not Walk) And this is not just my opinion. When tested in a gait lab, the run is biomechanically better than the walk.3 The walk is a persistent, early-learned habit and you cannot change a habit by working the habit. You do not learn to walk better by walking badly.

Novelty & Challenges Stimulate Neuroplasticity

Older children and teens that are coached in adapted sports programs can improve both their running abilities and their walk. Watch Paralympic athletes with CP play soccer! You do not have to be able to walk independently to improve functional levels. More involved children can learn to run holding on to a treadmill or by using gravity reducing technologies like the LiteGait. (https://www.litegait.com)

The novel challenge of running pushes the child out of the same old, same old habitual way of walking by activating more brain to figure out how to do it. Deep water jogging in a Wet Vest is another easy way to stimulate the brain. (Basic Water Exercise Program) If a child with hemiplegia only uses one side of their body, they just go around in circles. If a child with diplegia doesn’t use their legs equally, they do not move forward. Even adults with athetosis can use water exercise to learn to move all 4 limbs and ultimately walk better. (Deep Water Jogging for Gait Training)

Our brains are problem solvers and they respond to novel, challenging activities that take them out of habit. General George S. Patton could have been teaching 21st century neurorehabilitation when he said… “Never tell people HOW to do things. Tell them WHAT to do, and they will surprise you with their ingenuity.”

There are many ways for brains to solve problems and the older the child, the more options they have.

As ever, I welcome your comments and suggestions.

- Steven E. Hanna et al. “Stability and decline in gross motor function among children and youth with cerebral palsy aged 2 to 21 years.” Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology, 51 (2009): 295-302.

- National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, Cerebral Palsy Information Page, http://www.ninds.nih.gov/disorders/cerebral_palsy/cerebral_palsy.htm, (accessed Jan. 9, 2016).

- Jon R. Davids, Anita M. Bagley and Matthew Bryan, “Kinematic and kinetic analysis of running in children with cerebral palsy.” Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology, 40 (1998): 528-535.

Brains never cease to amaze. I once had a Young client with a very progressive type of leukomalacia which limited her lifespan to 3-4 yrs. Even as I noticed the presentation of balance disturbance when she looked up, she was developing a new gross motor skill – jumping.

I love reading your blog and can’t wait for your new book (I pre-ordered last night)! My 1 1/2 year old son has cystic PVL but the sky is still the limit!