The Good – The first 3 to 4 years are a period of active neuroplasticity in humans. Brain growth is explosive and there are many available neural networks. One of the best examples of early neuroplasticity is the exposure to language. If a child is raised hearing 2 or more languages, they are able to learn them all. In certain areas of Switzerland it is commonplace for children to be fluent in 4 to 5 languages. We all know that attempting to learn a second language later in life is much more difficult. This early neuroplasticity is one of the reasons that young brains recover better than old brains. The cases of complete hemispherectomy prove the point! (A New Way of Thinking About Recovery – Neuroplasticity Exists)

The Bad – Brains take 3-4 years to recover, and there does not seem to be any way to hasten the pace of recovery. In adult brain injury, it seems that most of the initial recovery is in the first six months and then the process slows down over the next year. Between years two and four, there are still significant gains, but they are slower and harder to achieve. The problem with babies is that they have to learn movement patterns at the same time that the brain is recovering. Over the first four years, all the lower order motor movements are learned. By four years, children can run, jump and climb without problem. From this point on, in the normally developing child, the changes in higher skill acquisition are dependent upon exposure. Early injury frequently interferes with the acquisition of lower order motor skills. These abnormal patterns of movement, learned early, become the recognizable patterns of cerebral palsy or incomplete BPI recovery. (Recovery In Cerebral Palsy Takes Time (and Fresh Thinking))

The Ugly – Whatever your brain does, it learns to do better. “Neurons that fire together wire together. D.O. Hebb.” The ugly part of this elegant, feedback system of development and recovery is that brains are not judgmental. If you have spasticity, your body over time will learn to be more spastic. If muscle strength and pull is unbalanced, bones, joints and muscles will grow abnormally. There are many distortional changes in the first four years because of the rapid growth rate in this time period. The child completes half of their adult linear growth well before their 4th birthday.

For the baby with an early neurologic injury, learning to move against gravity is accomplished with a damaged brain in the process of recovery. The abnormal habits of a small child feel normal to them. They are the only movement patterns they know and they’re quite comfortable with them. Does this mean that all their movements will necessarily be abnormal? NO, they are early maladaptive habits! Human babies do not come with hardwired movement patterns. The movements they learn later in life with a recovered, more mature brain, may be perfectly normal. (The Boy Who Could Run Better Than He Could Walk)

I am often asked if these early habits can be changed and the answer is yes, but it takes time and focused, intensive training. That means to change a habit you have to wait until the brain matures. Small children will not be able to do the repetitive work that is required for skill improvement. For a firmly established habit, it seems you almost have to wait until the development of the frontal lobes with puberty. Abstract reasoning is one of the latest maturing parts of our brain along with the “executive functions” that allow the mature brain plan into the future and to be able to self-motivate to do the repetitive work of skill training.

Younger children can do skill training in music, sports, or even chess, but the motivation is usually external in the form of a parent or coach. I am a strong advocate of techniques like CIMT (Constraint Induced Movement Therapy) and focused intensive periods of bilateral hand training. Both of these therapies have been shown to be helpful in improving function…and changing habits. However, along with therapies that teach better movement patterns, it is of crucial importance to prevent or constrain abnormal growth of the body and limbs.

Alignment means keeping the bones, joints and muscles growing as close to normal as possible. If the body distorts, the movement pattern will be more abnormal. This means using more taping, TheraTogs, braces and splints, including night splints…whatever is required to keep the limbs straight. This concept is not new. Athletes will not exercise or compete with a joint out of alignment. Just watch your favorite professional athletes and you’ll see wrist, elbow, knee and/or ankle supports, all designed to keep the body in proper alignment during the sport.

Now, here are the facts…body distortion occurs as a side effect of cerebral palsy as the child grows. Long-term follow-up studies show that this body distortion contributes to chronic musculoskeletal pain as a significant disability in a high proportion of adults with cerebral palsy. In spite of this knowledge, the use of proper alignment supports is approached in a semi-optional manner by both therapists and parents. I cannot tell you how many times I have been told, “Johnny doesn’t like his brace”. Or another favorite, “Beth won’t wear her splints because it makes her look different”.

In my world, young children do not make decisions that will impact their future health and function. Equally I do not know any parent who would willingly do something that leads to pain in their child. It is time for a frank and open discussion about this issue. I believe that if parents know the long-term outcomes, the compliance with prescribed orthotics will be a whole lot better.

Who wears a splint 24/7? There are a few great examples in the orthopedic surgery world. Babies born with congenital hip dysplasia wear a special diaper splint for several years to allow their hip socket to develop normally. Imagine how difficult this is for a new mother and father to manage, 23/24 hours a day.

Who wears a splint 24/7? There are a few great examples in the orthopedic surgery world. Babies born with congenital hip dysplasia wear a special diaper splint for several years to allow their hip socket to develop normally. Imagine how difficult this is for a new mother and father to manage, 23/24 hours a day.

http://www.yalemedicalgroup.org/stw/Page.asp?PageID=STW027102

Legg Perthes is a disease that hits the older child’s hip, causing a necrosis or death of the head of the femur. Luckily, it can recover into a normal hip bone, but only if it is held in place and molded to the correct form. This means the child wears this type of a splint for years. This is an image of Cameron Mathison, actor and Good Morning America special contributor, showing the brace that he had to wear, night and day, for 4 years!

Legg Perthes is a disease that hits the older child’s hip, causing a necrosis or death of the head of the femur. Luckily, it can recover into a normal hip bone, but only if it is held in place and molded to the correct form. This means the child wears this type of a splint for years. This is an image of Cameron Mathison, actor and Good Morning America special contributor, showing the brace that he had to wear, night and day, for 4 years!

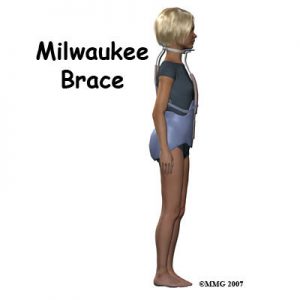

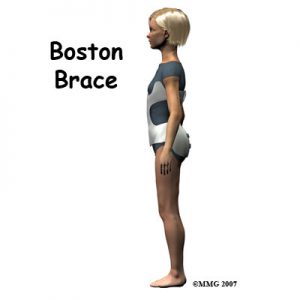

My last examples are the Milwaukee and the Boston Brace for idiopathic scoliosis. This problem is more common in young girls and again, they have to wear this bulky brace for years.

http://www.orthopediatrics.com/docs/Guides/scoloisis.html

In all these situations, the long-term outcome is clearly explained to the child and the parents. The goal is cure and the parents understand that it is necessary for their child’s best outcome. In the past, the goal for children with cerebral palsy has been set at functional independence. The new reality of human neuroplasticity means that the goal is set too low for many of the children.

What do you need to do if parts of your child’s body are not growing straight? Just like the parents of children with hip dysplasia, Legg Perthes disease or Idiopathic Scoliosis, I think you have a clear choice in front of you. The question is whether your goal is “good enough” or “personal best”? In my experience, growing the body in alignment is the first and most important goal of therapy.

The people to talk with are your therapist and surgeon and/or doctor to find out which alignment options are available in your area and what would be best for your child. If what you have now doesn’t fit, get it fixed. If high tone is the problem making an orthotic uncomfortable or ineffective, get a spasticity management assessment. The one thing that I can guarantee is that if the body is out of alignment, it will get worse as the child grows. The time to make this problem a priority is now.

In all these situations, the long-term outcome is clearly explained to the child and the parents. The goal is cure and the parents understand that it is necessary for their child’s best outcome. In the past, the goal for children with cerebral palsy has been set at functional independence. The new reality of human neuroplasticity means that the goal is set too low for many of the children.

What do you need to do if parts of your child’s body are not growing straight? Just like the parents of children with hip dysplasia, Legg Perthes disease or Idiopathic Scoliosis, I think you have a clear choice in front of you. The question is whether your goal is “good enough” or “personal best”? In my experience, growing the body in alignment is the first and most important goal of therapy.

The people to talk with are your therapist and surgeon and/or doctor to find out which alignment options are available in your area and what would be best for your child. If what you have now doesn’t fit, get it fixed. If high tone is the problem making an orthotic uncomfortable or ineffective, get a spasticity management assessment. The one thing that I can guarantee is that if the body is out of alignment, it will get worse as the child grows. The time to make this problem a priority is now.

You do not have to just take my word for this. Read some of the references below or talk to an adult with CP. I recently talked to an impressive group of adults at the annual meeting of the CP Group held in Washington, DC. (www.thecpgroup.org) Pain was a significant topic of discussion. It was difficult to see these intelligent, competent adults dealing with problems that in large part can be prevented with currently available technologies and treatments. They did not have a choice. Their treatment options were limited. There have been major improvements in medications, therapies and technologies in the last 10 to 20 years. We all owe it to the adult survivors to use what is now available.

References

1. Vogtle L. Pain in adults with cerebral palsy: Impact and solutions. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology 2009; 51 s4: 113-121

http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1469-8749.2009.03423.x/full

2. Schwartz L, Engel J, Jensen M. Pain in persons with cerebral palsy. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation 1999; 80: 1243-1246

http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0003999399900230

3. Jahnsen R, Villien L, Aamodt G, Stanghelle J, Holm I. Musculoskeletal pain in adults with cerebral palsy compared with the general population. Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine 2004; 36: 78-84

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15180222

4. Opheim A, Jahnsen R, Olsson E, Stanghelle J. Walking function, pain, and fatigue in adults with cerebral palsy: a 7-year follow-up study. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology 2009; 51: 381-388

http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1469-8749.2008.03250.x/full