Spasticity in cerebral palsy becomes worse with body growth, BUT if you are prepared, the damage can be lessened.

Birth to 4 years – The First Critical Period

Between 2 to 4 years of age, children reach half their adult height. This is also the time period when spasticity first develops. As the body grows, the muscles become tighter. By the time they are 4 to 6 years of age, children with cerebral palsy have developed the typical patterns of spasticity.

The Brain is Getting Better; But the Body is Getting Worse

Yet we know that during this time, the brain is actively growing, repairing and reorganizing to restore function. At first glance, this does not make sense. I admit that this apparent contradiction took me years to resolve.

Age 4 years to Puberty

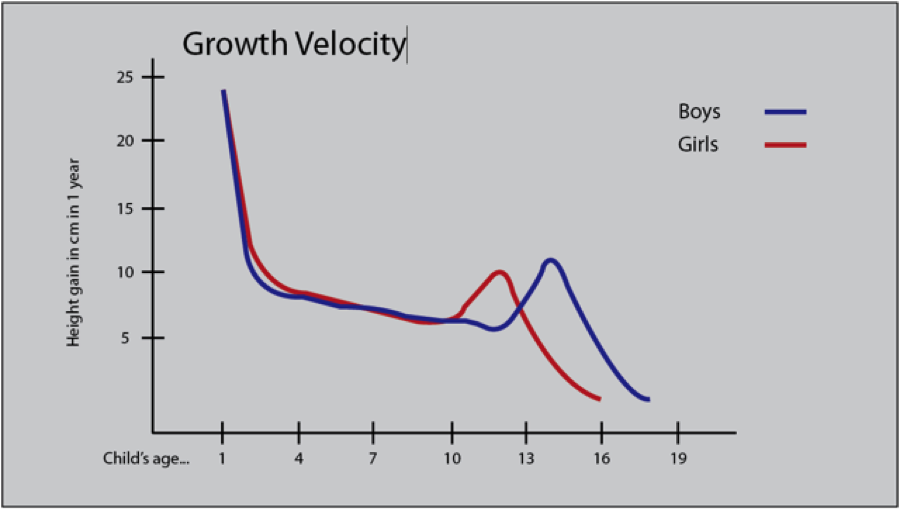

Grow velocity slows in this time period. The diagram is a smoothed average curve. Yet reality is very different. Every parent knows that children grow in sudden, rapid spurts. They notice that their child eats and sleeps more, they need new shoes and their body tightens further!

Why?

By this age, the first burst of neuroplasticity is over and the brain has repaired to whatever extent that it can. Yet the spasticity keeps getting worse with each growth spurt!

The puberty growth spurt is often the worst!

Growth velocity becomes ballistic again as the child moves through puberty. Again, this does not make sense as the brain is still improving with a second peak of neuroplasticity. Traditional thinking is that spasticity in cerebral palsy is a direct result of brain damage or malformation. I agree that the altered brain circuits initiate spasticity, but this is only part of the story.

Body Growth Requires Better Management

Most of the problem is a question of timing. Currently, active management of increased tone is too little and too late. Even though the peak growth periods are known, in most cases, spasticity management is started after it has gotten worse. Next week I will write about managing alignment through growth periods. The results can be dramatic.

If you want to read more about this right now, in Chapter 10 of The Boy Who Could Run But Not Walk: Understanding Neuroplasticity in the Child’s Brain I lay out a new theory of spasticity after early brain damage that demonstrates how doing the right thing, at the right time, and in the right order can dramatically improve outcomes.