Spasticity is a term used to describe tone changes that are common in cerebral palsy. Unfortunately, it is a generic term that is effectively useless when applied to a specific child. Pneumonia is another example of a generic term that without further definition, is of little value. Pneumonia may be a mild viral infection or SARS that kills in days. Spasticity severity ranges from only a mild stiffness experienced when learning new tasks to a total body event that limits movement. The next few posts will tackle the problem of spasticity in its common forms.

I am going to start with “simple” extensor tone in the legs, which is a problem for most children with CP. The first important point is that spasticity exists in a continuum of increased tone – think of it as a sliding scale of 1 to 10, where 1 is minimal tightness in the legs and 10 is rigid, crossed legs with any attempt at movement.

The next step is to figure out how much spasticity there is in an individual child. For example, a child with mild diplegia, affecting both legs, may be able to stand quietly with the heels down, but the same child will be up on his toes when he tries to walk or run. A moderately affected child might be up on his toes all the time, but the excess tone may be controlled by using a brace like an Ankle-Foot Orthosis (AFO). With mild (1 to 3) and moderate (4 to 6) levels of spasticity, the tone will vary during the day. It is higher when the child is tired or upset and lower when he is rested and not trying to move. When the child is learning a new movement skill, the tone usually goes up. In most children, the tone is normal during sleep.

In the more severe forms of spasticity, the tone is higher and more constant throughout the day. These children are at 7 to 10 on a 10 point scale of spasticity. Knowing where your child or the patient you are about to treat fits on a 1 to 10 scale of increased tone is important. In my experience, those children who range in tightness between 7 to 10 need active intervention by a Spasticity Management Team. I have seen so many families try and try again to avoid spasticity interventions like a posterior Rhizotomy or a Baclofen pump, only to realize the usefulness of these interventions when there are significant orthopedic complications that do require surgery. Getting a referral to such a clinic does not necessarily mean that you are going to go forward with either intervention, but it is worthwhile finding out the current research results and the team’s child specific recommendations.

I have already written that I feel all children with cerebral palsy should have an active twice daily stretching program that includes warm-up. This is basic maintenance like brushing your teeth. Further quick stretches during the day are very helpful, particularly after inactive time. A child who is always tight does not know what it feels like to have relaxed muscles. One of the things that people report, after a few weeks of regular daily stretch and massage, is the child starting to ask for this treatment as they start to recognize the difference between tight and looser muscles.

What about other interventions? I cannot prescribe for an individual child that I have not seen, but I can offer general advice based on 30+ years of following children from birth through to young adulthood. I can see a gradual shift in my own opinion over the years from less to more invasive. I see the same trend play out in my teaching experience. Those therapists who only work in an early intervention or young childhood practice also tend to be enthusiastic about functional interventions and do not stress braces, orthotics, or splints nearly as much as those who have the care and management of older children and teenagers. The early enthusiasm for a specific therapy method… many of which actively discourage the use of any bracing… falls away with the reality of bodily growth. Why?

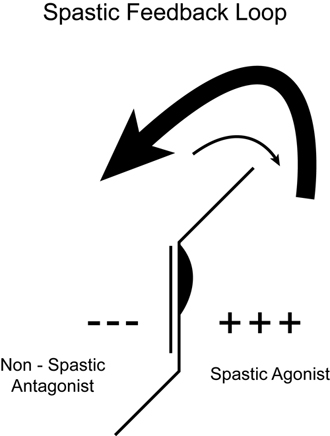

The answer’s simple. Spasticity in cerebral palsy develops over the first few years of life. In the newborn, spasticity is rare. The most common abnormality is low tone. The babies are weak and floppy. The cluster of changes that we call spasticity in cerebral palsy evolves with growth and movement against gravity. During the first 2 to 4 years of life, the baby grows to half their adult height. This rapid growth rate in the presence of unequal muscle balance causes bodily distortions. At the same time that the body is distorting, the brain is “wiring in” a movement pattern of walking up on tip-toes. Everything in the body works on a positive or negative feedback cycle. The more a child is up on their toes, the tighter the muscles of the back of the leg and the more inhibited the muscles on the front of the leg. We see changes in muscle length with a short, weak spastic muscle group and an opposing or antagonist muscle group on the opposite side of the joint that is elongated and even weaker. (Muscle Imbalance Hurts Growing Bodies) The changes are not confined to just the muscle and tendons. The brain learns to fire the spastic muscles earlier and more completely than the relatively inhibited antagonist muscles.

The diagram to the left shows the overactive spastic muscles that tend to pull the ankle up and the weak, inhibited muscles on the front of the leg that lose the ability to pull the toes up. The arrows indicate that the inhibition arc of the feedback loop grows stronger as the neural networks become facilitated. The ability of the brain’s neurons to fire the muscles in the opposing direction is also weaker. This simple relationship explains why spasticity gets worse every time the child grows.

Stop and think about it for just a moment. All the experts agree that the brain problem that causes cerebral palsy is not progressive. Yet everyone realizes that the impairment does progress. Further, when children have orthopedic surgery to manage the secondary effects of untreated spasticity, the tone goes down. The change in spasticity is particularly obvious in children who have multilevel orthopedic surgery, pioneered by Dr. Jim Gage. The surgeons change the length of the muscles and reorient the bones. They go to great lengths to not cut the nerves. Yet when the child’s body is put back into better alignment, the spasticity decreases. Is it not logical to think that if we use more bracing, orthotics, and splints early on to maintain alignment, the children might do a whole lot better?

More on this next week with a discussion of supports and Botulinum injections. Your homework for this week, if you choose to do it, is to figure out at different times of the day and week where your child fits on a spasticity range from 1 to 10. Do these assessments without anything additional on their bodies and get an idea of how many times they are up on their toes or walking in a crouch gait. The following are some of my previous posts in this spasticity series and a few related posts close to this topic. I welcome your comments and questions.

See Also in the Spasticity Series

Muscle Imbalance Hurts Growing Bodies

What About Spasticity?

Related Posts

Back To Basics – Alignment Comes First

Early Alignment Pays Dividends

Billi Cusick’s Thoughts on Managing Children with Spastic Diplegia

Is Malalignment Malpractice?

Hi Dr Pape,

There is a lot more recognition of the non-neural tone these days, which relates back to your comments on how the shortening of the muscle (and fascia) contributes to the overall pattern and severity of spasticity. Do you use that term? I like it because it emphasizes the fact that not all the spasticity and deformities associated with cerebral palsy are caused by the brain lesion. They are often secondary affects and it’s good news because although we haven’t yet figured out how to “fix” the brain lesion, the secondary affects are often preventable – as you have explained so well in some of your related posts.

I think the term non-neural tone is a good one and I would take it one step further. The brain lesion starts the complex of signs and symptoms that we call spasticity, but the non-neural tone is what perpetuates it. The recovery of normal tone in older children post surgery seems to indicate that if we spent more time inhibiting the expression of high tone with appropriate support and attended to the non-neural component, the children would do a lot better.

A great post … And not just because emphasis on stretching is such a large part of my work with neuro-motor challenged kids and I appreciate your clarification of its role in a good program. But because it really lays bare the sad fact that the lack of biomechanical supports leads to more serious obstacles to fully exploiting neuroplasticity.

I find your blog very interesting. I am the mother to a 2yr old hemiplegic spastic cper, and like you had stated above, I was always told that things would not progress in terms of her CP. I find it very eye opening to hear a doc say that while the actual brain damage may not progress the secondary affects will. I appreciate that. It wasn’t until I started poking around myself that I can feel like I can understand and have a decent convo with our therapists. I really appreciate the “allowed”, “how to”, spacticity management team talk, I can really understand you. You seem to put things in terms that us “simple” folk can understand. Don’t get me wrong, I have always been sent home with “homework”, but couldn’t really understand it. Again thank you

Thank you for the kind comments. I always told my students that their only goal was to help the parents of a child with a problem turn into a World Class Expert in their child’s diagnosis. If you do not understand what you are being told, that is the problem of the teacher, not the student.

Thank you for this very interesting post. My child’s doctor wants to wait until she is at least 2 years old for Botox and wants to do only AFOs in the meantime (she is now 19 months and hasn’t had AFOs yet). I don’t want to wait as I feel the Botox in addition to the AFOs could help her learn to walk more normally. She has mild spastic hemiplegia and is getting near to walking independently but not quite yet. What is your opinion on Botox for young children/babies under 2 years old?

Joelle,

Thank you for your comment. Botox is only approved for use in CP at age 2 years. I would agree with your doctor that you should try the AFOs first. This is a post about Billi Cusick’s newer method of AFOs that you might find interesting. Your therapist could try out a temporary lift in his shoe to see if it might help before you discuss this with an orthotist.

http://www.karenpapemd.com/a-new-way-of-thinking-about-afos-spasticity-series-6/