Puberty can be a second chance or a complete disaster – the outcome depends on the choices you make during this important period. Unfortunately, to take advantage of this period of enhanced neuroplasticity, your teenager needs to become an active participant. This may be difficult as the teenager is busy growing a new brain.

Regional Maturation of Cortical Thickness: Ages 4–21 Years

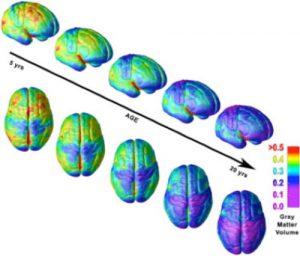

Right lateral and top views of the dynamic sequence of gray matter (GM) maturation over the cortical surface. The side bar shows a color representation in units of GM volume. [Reprinted from Gogtay et al. (2004).]

The image shows the sequential maturation for the GM in blue. The brain matures from the back to the front, with the earliest changes in visual areas at the back of the brain and the latest in the pre-frontal cortex at the front of the brain. This is the part of the brain that is responsible for “adult” thought processes. The teenager gradually develops abstract reasoning, improved executive functions and most importantly, the ability to self-motivate to reach a distant goal.

These are all good changes, but it can be a very confusing time for the teenager. Over a relatively short period of brain growth, their world-view changes dramatically and this can be challenging for the entire family, especially if the transition is complicated by any form of special needs or medical challenge. Children with an early neurological injury need more care and attention from the start and as a result, most parents fall into a “caretaker” mode, working hard to fulfill their child’s needs for support and therapy. It is not surprising, that after this start, it may be harder for parents to “let go” of their caretaker role and allow their teenager to make independent choices. Most will make a fair number of “mistakes” on the bumpy road to maturity, but it is all part of the learning process that leads them to personal responsibility.

The teenagers’ demand to have their own opinions validated is both terrific and terrible, because this time period is also the last active period of body growth. Growth velocity varies, but generally the faster they grow through puberty and the bigger they get, the more biomechanical problems will develop. This is the nexus of the problem – the teenagers’ desire for more independence and decision-making is confronted by the reality that parents need to push for more therapy and more disruption of day to day living. The challenges are great but so are the rewards. If both parent and teen can be motivated to work hard with focused intensive therapy, it is possible to correct many of the existing alignment problems and even allow further improvements.

These are the key points to keep in mind. Doing “more of the same harder” will not lead to a different outcome. The teenager is right to refuse more of the same form of therapy. They have done it for years and to them it was a waste of time…they still have problems and do not realize how much worse they would have been without all the work and effort already expended. They are right, but somehow, we have to help them understand that all the available research confirms that the majority of teenagers can, at best, stay the same and most gets worse. Something needs to be done.

The first and most important step is to get your teenager to “buy in”. I would start with an explanation of the changes to be expected as they grow. Have them read the blog posts in the Alignment Category for a start, then book a review appointment with your orthopedic surgeon and/or CP doctor. See what these professionals advise re: treatment and prognosis. These appointments should produce both a problem list and a treatment plan. The next step is to ascertain what the teenager considers a problem. Make the list as honest and as complete as you can. Figure out what makes each problem more troublesome and what makes it less of a problem.

Some Examples:

– There is increased spasticity when she is tired or after sitting a long time. It improves when she is rested or after a massage and stretch.

– His speech is better at home than in public, in front of strangers.

We are all so used to looking at what is wrong with a movement or behavior that “Catching them doing it right” takes a little practice. You will find that each skill has a range of behavior that varies between best and worst performance. As a start, just making his or her best behavior more consistent can be life changing. (Uncover Recovery Hidden by Habits)

Whatever the level of their current “best” performance, it can be improved by targeted, intermittent, intensive training. Think of the change in performance achieved at a hockey or tennis camp. Three to six weeks of focused, intensive work on a goal that is important to the teenager will succeed and almost magically, motivation to change becomes a reality. Intensives also work with younger children and it is easier to gain their co-operation.

The major impediment to doing an intensive, once you understand the possible value of the method, is cost and time constraints. More on this next week.

Additional Reading:

Giedd JN, Rapoport JL, Structural MRI of Pediatric Brain Development: What Have We Learned and Where Are We Going? Neuron. Sept 2010;67(5):728-734

Gogtay N, et al. Dynamic mapping of human cortical development during childhood through early adulthood. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004 May 25;101(21):8174-9. Epub 2004 May 17.

Related Blog Posts

Activity Dependent Neuroplasticity – Making & Replacing Habits

Note – This post has a terrific animation that will help older children and teenagers understand how habits change their brains and that maladaptive habits are not carved in stone.

Take advantage of the Periods of Peak Neuroplasticity

Note – This explains the changes in brain growth and parental expectation over time.

Hi Dr. Pape,

Writing from Spain. Thanks for an amazing website that has positively changed my views on my daughter’s recovery and has shown me where to start and where to go (core stability, alignment as the base)

We have a 9 month baby who fell off the bed about two months ago and suffered an ischemic stroke and left side hemiparesis, very few seizures, only two or three right after the fall, none since, but still on Kepra.

Though she’s been amazing at recovering and we’re really pleased, I see a continuing weakness on her left arm. My question is: do you think it would be a good idea to use “weights” in a baby? I was thinking a wristband with a bit of weight or a metal plate placed on the skin parched with some kinesiotape. I guess my question is if this is at all a practice done in your field at such an early age. Thank you.

I do not know of any study, but it is a reasonable idea. I use wrist weights in the older child. I wonder if a splint may have the same effect and also keep the wrist and hand in good alignment. Bright colours on it will also attract your child’s attention to the hand.